One of the invisible but critical roles of a gameplay programmer is making design decisions that haven’t been explicitly defined. Often, the design spec stops at the “what”, and it’s up to engineering to decide the “how” and those “hows” can subtly shape the player experience in ways no one else on the team might even be aware of.

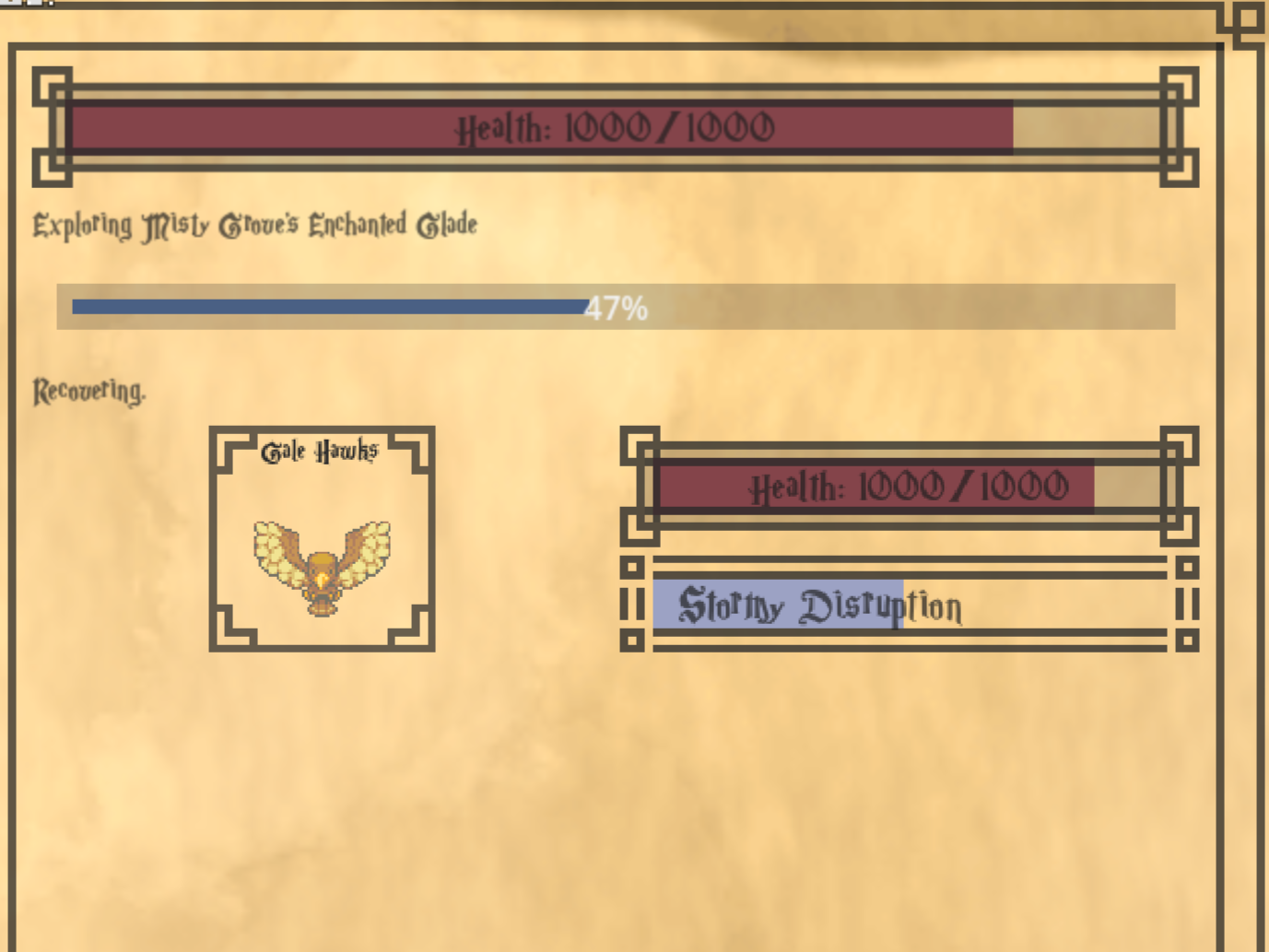

Here’s a practical example from my work on an idle RPG combat encounter system, where the player can engage with varying numbers of enemies in quick, automated battles that run even while they’re viewing other menus.

A Subtle Design Decision Hidden in Code

Take a look at the Update() function that runs a combat encounter:

public override void Update(float dt)

{

if (IsEnded) return;

foreach (var player in PlayerGroup) player.Update(dt);

for (int i = EnemyGroup.Count - 1; i >= 0; i--)

{

if (EnemyGroup[i].IsDead)

{

DropsToReward.AddRange(EnemyGroup[i].Drops);

EnemyGroup.RemoveAt(i);

}

}

if (EnemyGroup.Count == 0)

{

End(EResult.PlayerSuccess);

return;

}

foreach (var enemy in EnemyGroup) enemy.Update(dt);

for (int i = PlayerGroup.Count - 1; i >= 0; i--)

{

if (PlayerGroup[i].IsDead)

PlayerGroup.RemoveAt(i);

}

if (PlayerGroup.Count == 0)

End(EResult.EnemySuccess);

}

Looks simple enough but notice the order of operations. We process the player group first, then the enemy group. That’s not accidental.

Why Processing Order Matters

In this system, Combatants (both players and enemies) attack and update independently based on timers and parameters. In tight timing windows, particularly when multiple units are on the brink of death, the order of evaluation determines who gets the last hit. If both sides would technically die on the same frame, the one processed first wins.

This creates a tiny, almost imperceptible edge. So the question became:

Should players or enemies be given that advantage?

Designing for Favorable Perception

Even though most players may never consciously notice this difference (these encounters often resolve in seconds and may not even be onscreen), I made a deliberate choice to favor the player.

By processing the player group first, they get the chance to defeat enemies before enemies get to retaliate in those edge cases. It’s a small gesture, but it reinforces the sense that the player is winning fairly and has agency, even in an automated system.

Low Cost, Low Risk, Positive Payoff

This change required no additional systems just a small reordering of logic but had a positive potential impact on perception. In a game where combat is only part of the broader gameplay loop, this was a small implementation detail that supported the player fantasy without disrupting system balance.

When to Loop in Design

In this case, the tradeoff felt isolated and low-impact across systems. I didn’t escalate it to the design team. But I always consider the scope and systemic consequences of decisions like these. If the outcome had broader implications (e.g., affecting XP gain rates, loot balance, or story gating), I’d absolutely bring it to a designer or, if I’m also wearing that hat, pause to reflect more deeply on the intended player experience.

Takeaway

Not every design decision starts in a design doc. As a gameplay programmer and technical designer, it’s my job to bridge gaps between implementation and experience, thinking not just about whether something works, but how it feels even when no one’s looking.